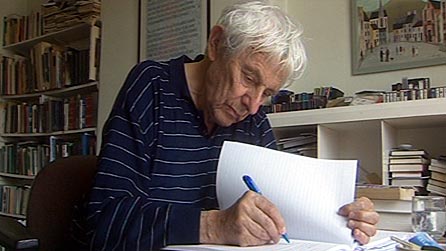

A writer must cultivate their inner editor. Often, I’ll query an aspect of a story with the author and they’ll say, ‘Yes, I didn’t get around to dealing with that’ or ‘Did I leave that in’? Their inner editor whispered a note and they screened it out. It’s perfectly natural to screen out the voices that speak of faults in your work. Without these screens, we’d give up on the first page. But as the manuscript builds up, and the redrafting begins in earnest, notes from the inner editor are vital.

Cultivating sensible criticism of your work is crucial. Part of this is learning how to listen to informed criticism. Prior to submission for publication, I redrafted The Red Men after a few notes from my agent. She told me to reduce the amount of swearing in it and to ditch the original title ‘Leave My Soul Alone’, a quotation from a disturbing poem by the doctor-poet Dannie Abse about an operation for a brain tumour; as the surgeon’s probe blindly pushes its way through the brain in search of the cancer, the conscious patient suddenly begins to speak. It’s so arresting I’ll just take a moment to quote the pertinent verse from ‘In the Theatre’:

‘Then, suddenly, the cracked record in the brain,

A ventriloquist voice that cried, ‘You sod,

Leave my soul alone, leave my soul alone,’ –

The patient’s dummy lips moving to that refrain,

The patient’s eyes too wide. And, shocked,

Lambert Rogers drawing out the probe

With nurses, students, sister, petrified.’

So I had reasonable literary reasons for calling the novel ‘Leave My Soul Alone’ as I was likening the colonisation of the mind by digital technology and media to the blunt early era of brain surgery, but I had not considered how ridiculous the title may appear to other people coming cold to the book. Of course, part of me will never give up that title, will always maintain that it has some value; every novel is the consequence of a dozen major decisions and a hundred thousand minor ones, and the ghostly advocates for those various positions persist in the author.

When I was discussing the novel with my agent, I spoke about how pleased I was with the writing in chapter four, a big section of back story set in the Scottish island of Iona. My agent made a face. I now know what that face meant: did I really want a big section of flashback at that point just as the plot was getting going? What happens on the island of Iona, and the characters who are introduced, only really begins to effect the action in the second section of the book. At the time, I was convinced the flashback was crucial. Perhaps having already persuaded me to change the title of my novel and to excise much of its profanity, my agent decided enough was enough for one session.

Re-editing The Red Men in preparation for digital publication, I’ve removed the entire chapter set on Iona. I may reinstate it later in the book at the point at which the characters introduced in this long flashback become more active in the plot. The only reason to keep it in is that it provides insight into the peculiar religiosity of Hermes Spence, the CEO of Monad, and his interest in gnosticism, all of which pays off at the end of the book.

Writers need their inner editor because sometimes, these days, publishing does not provide an outer editor for them. Concerned primarily with how the book will play in the marketplace, a publisher can be indecently indifferent to a work at the level of the sentence.

Not always though. For my non-fiction book The Art of Camping I sat down with my editor Juliette in a coffee house in Lewes. She put the manuscript between us and turned it slowly page-by-page. For the sections, she was happy with, the speed of the page turning increased. For the sections she felt could be improved, the page turning slowed to a crawl, creating a kind of silence that my inner editor felt compelled to break: ‘You’re right,’ I would say, unable to take the incredibly slow page-turning anymore, ‘perhaps that section could lose some of the historical detail. Perhaps I could add some more present day amusing memoir material in to break it up.’ The technique was skilful, forcing me to admit what I already knew but had not been able to face. It’s one of the hardest truths for a writer to deal with: that more work is required.