I have finally learnt to swim properly. For months, I have been gamefully thrashing away with a breaststroke undeveloped since the mid-1980s, keeping my head above water at all times and exiting the pool with a distinct pain in the neck. This style of breaststroke, in which the swimmer attempts to preserve their hairdo at all cost, served me well on the three or four occasions, in the previous twenty years, that I exercised.

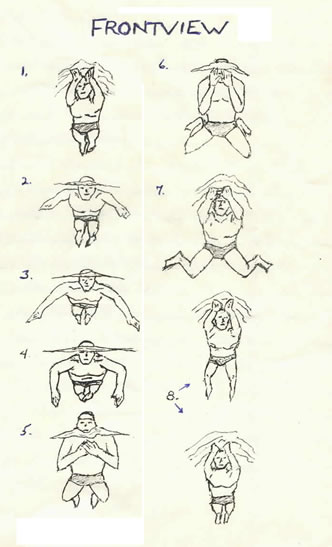

Now that I am forty, and attempting to outswim death, a more efficient stroke is required; after an evening with Google, some terrible advice from a content farm (“Inhale when your face is in the water, and exhale when it is out” – thanks eHow). and the purchase of some goggles, I did it; I stopped swimming like an old lady.

I glided alongside the proper swimmers in the grown-up lanes. Pausing for breath in the shallow end, I had a faint muscle memory. Something in my childhood to do with running with the big kids. No, not running. But something like running.

“The Frenchmen on the sun loungers were

hirsute and wore tiny speedos stuffed with

roadkill”

After changing, I sat in the leisure centre lounge sipping hot chocolate and the memory returned: boys cycling down Newlyn Avenue near to my family home, and me cycling to keep up with them. No, wait. Not cycling. I didn’t have a bike. Not then. I was five or six years old. The other boys were going so fast on their bikes and I was thrashing away trying to keep up, doing a kind of breaststroke. Surely not. How could they have been riding and I swimming?

To answer that question, we must inspect my trunks. I’ve been swimming four miles a week for five months and yet only last weekend did I buy a pair of goggles and – more crucially – a new pair of trunks. The elastic had withered on my old trunks and I was reduced to tying them in place with knotted boot laces. These old trunks had been purchased for a camping holiday twenty years earlier, pointlessly as it turned out, as the French swimming pools would not admit a man in boxer short-style trunks; the pool bouncer tutted his index finger at my big trunks and pointed approvingly at the various Frenchmen on the sun loungers; they were hirsute and wore tiny speedos stuffed with roadkill.

I had owned the trunks for so long and used them so infrequently that I forgot they were trunks at all. During a sweltering summer, I was talking to my girlfriend on the phone and observed that it was so hot that I had taken the risk of coming into the office – I worked at the Guardian at the time – in my shorts. “But you don’t own any shorts, Matthew,” said Cath. We used to call Cath the Truth because of the way she undercut our illusions. In this case, the illusion that the trunks were shorts and the further illusion that it would be acceptable to come to work at a national newspaper, even one as famously liberal as The Guardian, in them. I exited the office as briskly as my crouch permitted.

So we are stacking up questions here: why didn’t I own a proper pair of shorts? Why did it take me so long to replace a pair of twenty year-old trunks? If I am swimming five miles every week, why wait six months before buying a pair of goggles? And why did I have a muscle memory of doing the breaststroke down Newlyn Avenue when all the other boys were on their bikes?

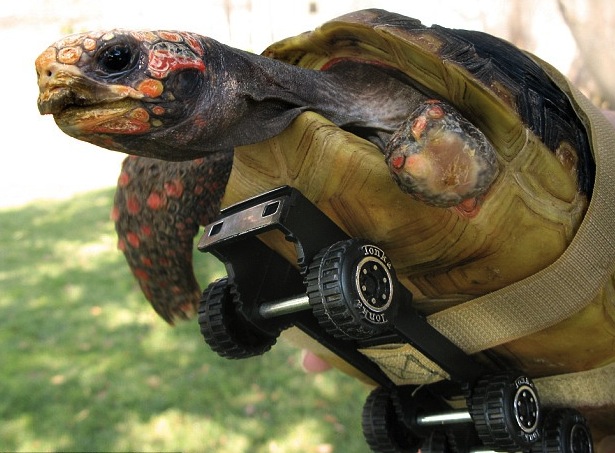

I was raised to be frugal. My mother believes in making the best of what you’ve got and not needlessly expending resources on fripperies such as trunks or bikes. This was why, when the other boys pedalled their unnecessary bikes down Newlyn Avenue, I luged alongside on a plastic turtle, its casters jiggling manically over the tarmac. The turtle was green. It could go at a fair clip, downhill. But it was never designed to be a mode of transport. The arm action required to power it was similar to the pushing down part of breaststroke, hence the muscle memory. Also there was something familiar in my desperation to keep up with the big boys despite being hopelessly under-equipped for the job.

When I got home after swimming, I told all this to Cath. She’s my wife now so she knows all about the turtle-that-was-not-a-bike.

“You’ve grown, though,” she said. “You can buy goggles now. You can recognise what needs to be done, and do it. You’ve learnt an important lesson for a forty-year-old man. Sometimes making do is not good enough. To preserve our dignity, sometimes we actually have to go to the shops.”