I had a quiet Christmas reading the various works of Paul Fussell. In his The Great War and Modern Memory, Fussell makes the point that the gap between the experience and rhetoric of the Great War gave irony greater prominence in British discourse. The irony arises from the loss of innocence caused by the hideous conflict. One index of the innocence of the Edwardian era prior to the Great War was a blindness for euphemism: “one could say intercourse, or erection, or ejaculation without any risk of evoking a smile or a leer.”

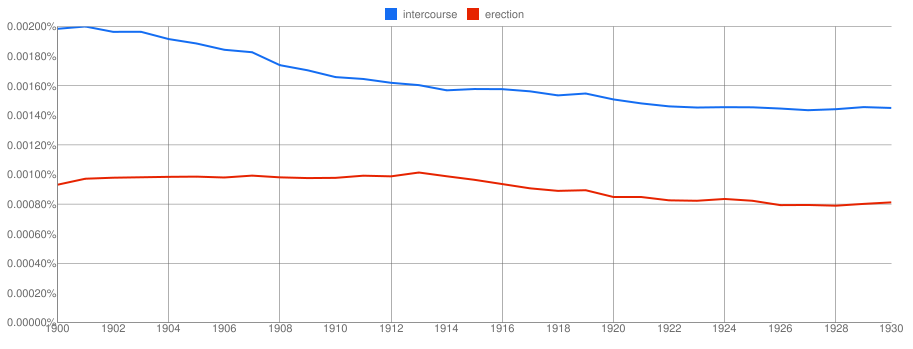

I tested Fussell’s theory by using the Google Ngram, which maps word usage.

As you can see from this graph, the number of erections peak just before the Great War, and thereafter declines across the decade.

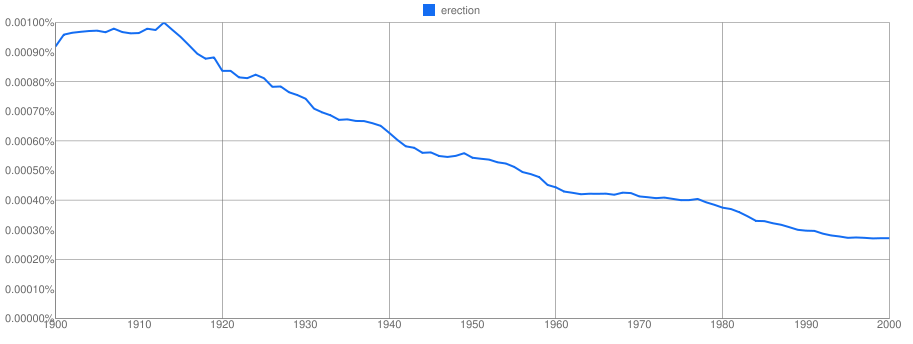

The decline continues across the rest of the twentieth century as erection sheds its non-sexual meaning.

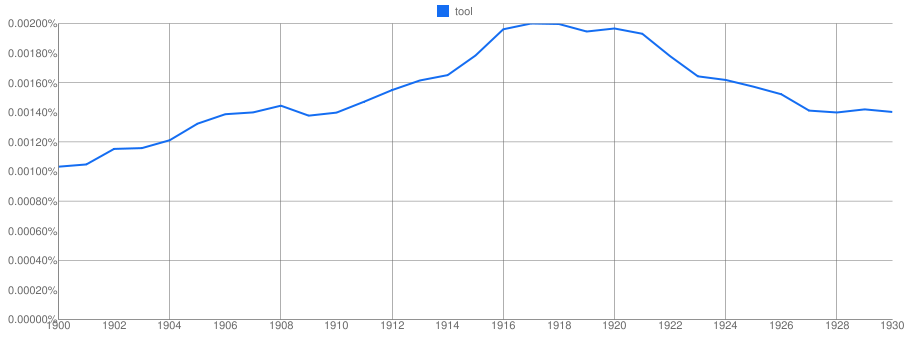

Fussell also notes Henry James’ innocent employment of the word “tool”.

The ngram for “tool” reveals a growth going into the war, with a dramatic shrinkage across the subsequent decade.