In The Red Men, the characters do not use computers, they use screens. These screens are pliable and can move around in response to haptic gestures or remote commands. They float on a cushion of air across the floor and can winnow out into a large landscape format or shrink down to fit into your palm.

“Gelatinous screens billowed out like spinnaker sails to catch the data pouring in.”

The novel was written just before the advent of the iTouch but I claim no special prophecy. Screen-based user interfaces were prevalent in SF and Bill Gates’ living room and appear in everything from Star Trek: Next Generation to Minority Report.

I made the screens soft. The prospect of a flexible quasi-organic screen fascinated me, and I visualised them as floating medusa jelly fish capable of exercising limited volition of their own. By the mid-section of the novel, robots wrap themselves in screens to project a different appearance. Characters are suffocated by these screens too.

Editing the novel this week in preparation for its digital publication, I‘ve been adding to the set of haptic gestures the characters use to operate the screens. With tablets we are accustomed to the swipe, the three-finger flick, the two-finger scroll. But why not a screen that sparks to life at the click of your fingers? Or a blown kiss? Or a beckoning index finger? When will I be able to stroke my screen and make it purr like a cat? Or whistle for it to come to me like a dog? Tomorrow presumably.

A useful repository of haptic gestures can be found in magic. The wave of a wand. The magic finger firing lightning bolts. ‘Open sesame’ combines voice recognition with security protocol.

Exploiting the potential of magic to conceptualise user interfaces is key to marketing the next generation of tech.

Apple already know this.

Uh, er…

Apple took Arthur C Clarke’s line that, ‘Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic’ as a guide for their design aesthetic. The copy for the iPad promised, “A magical and revolutionary product at an unbelievable price”. That’s three mystical promises in one sentence. People who are really into technology hate Apple because it promotes magical thinking and denies or conceals the reality of the tech.

The tablet or smartphone is anticipated by the black scrying mirror of Elizabethan magus Dr John Dee. In The Red Men, the futuristic company takes a sigil from John Dee as its logo. The title of Charlie Brooker’s science fiction TV series ‘Black Mirror’ closes the loop for us between tomorrow’s tech and magic.

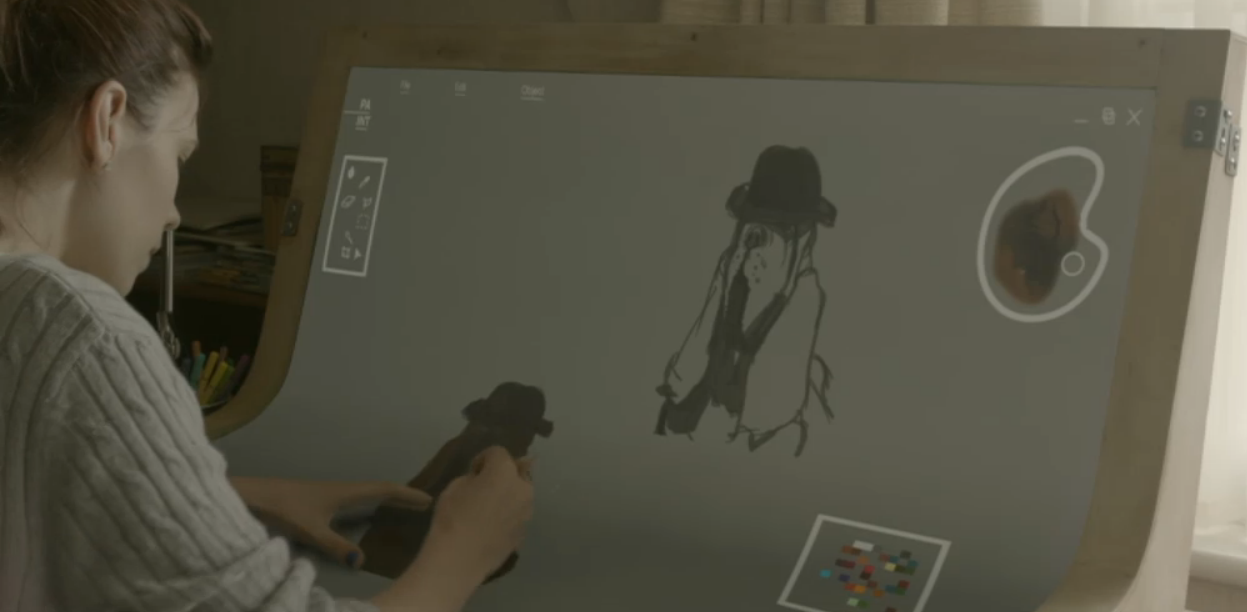

Someone invented a nice screen for the first episode of the second series of Black Mirror. Notice the character is using it to paint and draw and not to code. You will increasingly see advanced technology sold with images of craft and finger-painting and suchlike. It’s the best way to make the tech appear homely and modelled around the individual.

We will only recognise a technology as truly advanced only when it is wrapped and concealed with a layer of magic. No sooner had this thought coalesced than I was reminded of the copies of Harry Potter’s Book of Spells, an augmented reality Playstation game. Sell technology that helps you imagine yourself as a wizard.

Richard Matheson’s classic horror SF novel I Am Legend devises scientific explanations for the supernatural phenomena of vampires. It digs around in medical textbooks for plausible physiological explanations for vampirism. One of my favourite workshops with my science fiction students this term was asking them to devise scientific explanations for magical artefacts: I particularly enjoyed one student using quantum entanglement to explain how Voodoo dolls work. Superheroes mix up science gods and supernatural monsters; the co-existence of the magical with the scientific, of Iron Man and Thor, is a quirky paradox that is creatively generative for the Marvel Universe.

We divide science fiction from fantasy because one features magic and the other features technology that behaves like magic. Here’s Adam Roberts from his History of Science Fiction:

‘Science fiction, in contemporary publishing and bookselling practice, is distinguished from “Fantasy”, the latter involving fantastic or non-realistic form in which the mechanism for fantasy is magic rather than technology.’

Lord of the Rings revolves around a magical ring. The magic sword of Excalibur. Aladdin’s magic lamp. The next generation of digital accessories, that is, Google’s glasses, Apple’s watch, Microsoft’s handbag with a portable hole in it, will be magical implements.

Adam Roberts’ history of science fiction is founded upon ‘a historicised definition of SF as that form of fantastic romance in which magic has been replaced by the materialist discourses of science.’

One of the crucial decisions I made when writing The Red Man was whether to give in to the imaginative allure of magic which, in the late 1990s, roved around an axis of techno-narco-mysticism. In the novel, I used gnosticism as a cover for zealotry in the American power structure, whether it was the Christian fundamentalism of George W Bush or the anarcho-libertarianism of the tech gurus. That Gnosticism has a strong connection to science fiction through Phillip K Dick’s Valis experience only pushed me further down that path. In The Red Men, the artificial intelligence Ezekiel Cantor is understood by the Monad management in terms of their gnostic beliefs. The original inspiration for The Red Men was Kurzweil’s The Physics of Immortality, as succinct an expression of our desire to see, in the future of science, a way of fulfilling our mystical yearnings. The title of William Gibson’s Neuromancer makes the same point.

The Red Men is built around a dialectic of technology and mysticism, expressed in the rival yet inter-dependent companies of Monad and Dyad, two sides of one artificial intelligence. Looking back at my decision all those years ago to push the novel out into mysticism, I regard it now as a florid but permissible response to an abiding cultural dialectic, and not merely an unwarranted or ill-disciplined diversion.

Also, screens have moved on. And soon they will be moving on of their own volition.

I think you’re right on the money vis a vis technology and the magical *interface.* It’s not only the functionality of the thing that we deify, it’s the UI. And while there have always been set-apart gestures, implements, and even words to make the magic happen, subtlety seems (at the moment) to indicate an increase in power. We’re used to pressing the button (or, further back, throwing the switch) to make something happen, but how much better to casually swipe, almost as an afterthought? Or even just speak a command?

I was watching the trailer/demo/ad for Google Glass, and you apparently need to say “ok glass” as the abracadabra that lets it know you’re talking to it. And I wondered, isn’t that too much? People can hear you hide the rabbit in the hat before pulling it out! What about making Victor Borge’s “vocal punctuation” into commands, so that casual clicks and coughs and hums would capture video or text your BFF? Or as you say, even a form of breath? In short, I think the move to subtlety is key to portraying a believable futurism. At least from this present!

But also there’s the “aura” allegedly lost in the mechanical age. And not just for art. Invoking magical metaphors in the UI goes some way towards reviving the sense of aura in general, if not all the way to its unique URI. And the (projected? introjected?) aura compels our desire for it, that is in its nature, or at least its definition… perfect for consumers, as well as adepts.

I also think those gelatinous, flexible screens are upon us right now. Metaphorically of course. I don’t know anyone that isn’t completely wrapped up in their tiny portable screen; the particular app involved (text, email, WWF, “the phone itself”) seems less important than the all-consuming nature of the experience. And we pretend that we’re not looking at a little black (mirrored) box we carry around in one hand – awkward! Instead, we enter into a virtual world with the black box a forgotten threshold. So we’re already there, and the flexiscreens (&scattersuits) to come will be mere manifestation.

Although then again, maybe not that “mere.” Because how much further away will we imagine ourselves to be when we don’t need to imagine the environment, but will be literally wrapped in it?

I agree, the 90s were right, in their way. The ghosts have been in the machines all along. We put them there.